This article explains how to conduct a scoping review. If you’re interested in a free tool that helps you write literature reviews quicker, check out Avidnote.

A scoping review presents a relatively “new” approach to synthesizing research literature which is different from the traditional systematic review. The difference of scoping review concern primarily the purpose and aims of the review. With a scoping review, the primary goal is to give the reader an overview of the current evidence from the literature with respect to a specific research topic without giving a summary answer to a discrete research question. Scoping reviews are typically less exhaustive than systematic reviews. The general purpose for conducting a scoping review is to map and identify the available evidence (Anderson et al., 2008; Arksey and O’Malley, 2005)

Scoping reviews can be preferred to systematic reviews in cases where the review’s objectives include identification of gaps in knowledge, interrogating a body of literature, describing concepts, or scrutinizing research conduct. They can also act as useful precursors to systematic reviews (Munn et al., 2018) as well as help determine the suitability of inclusion criteria and likely research questions. Because of the exploratory nature of scoping reviews, it is not necessary that each review must be a holistic coverage of all the extant body of knowledge in the subject matter being reviewed.

What is a scoping review?

According to the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, scoping reviews are:

“exploratory projects that map the literature available on a topic, identifying key concepts, theories, sources of evidence and gaps in the research.”

A more extensive definition was given by Colquhoun, et al (2014).

“A scoping review or scoping study is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge” Colquhoun, et al. J of Clin Epi. 2014, 67, p. 1292-94

How to perform a scoping study in 5 easy steps

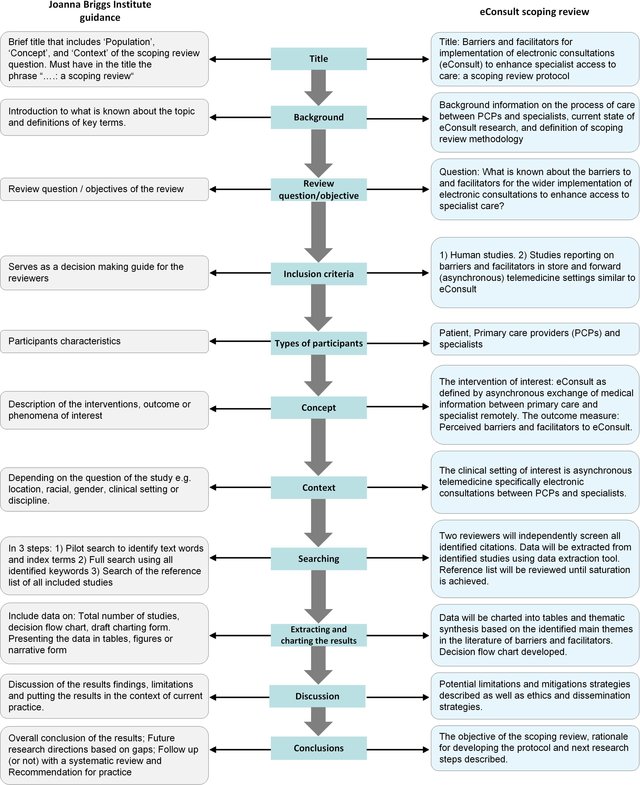

In the sections below, I intend to summarize the guidelines provided by the Joana Briggs Institute for conducting a scoping review.

Step 1 – Define the topic that you will be reviewing; its objectives and any potential sub-questions.

Step 2 – Develop a review protocol. The protocols functions as the plan behind your review. Here you’ll state eligibility criteria (for inclusion/exclusion), how you screened the literature and the charting process that you utilized.

Step 3 – Apply PCC framework

Step 4 – Perform systematic literature searches

Step 5 – Screen the obtained results and only include studies that meet your eligibility criteria

Step 6 – Extract and chart the data you extracted from the collected studies

Step 7 – Write a summary of the evidence to answer your research question(s).

The list above summarizes the process behind performing a scoping review. Below, we elaborate further, based on recommendations from the Joana Briggs Institute.

Title of the review protocol

The suggested length according to JBI of the length for the introduction section of the scoping review protocol is roughly 1,000 words. The protocol (and the review itself) should have an informative title that helps shed light on the topic of the scoping review. To this end, the phrase – “…: a scoping review” should be attached to the title. Such an attachment will enable readers to easily have an idea of what the document is about. Be sure to include the word “protocol” if that is what the document is about.

For example, “Assessing the impact of treating anxiety using nigella sativa: a scoping review protocol.”

You should also avoid constructing titles in question format. The Joana Briggs Institute (JBI) recommends a “PCC” mnemonic to help in generating a clear and meaningful title for a scoping review. The acronym PCC stands for population, concept, and context. According to the Institute:

- the population aspect focuses on “important characteristics of participants, including age and other qualifying criteria.”

- concept may include details related to elements that would appear in a standard systematic review. Among such details are “interventions” and/or “phenomena of interest” and/or “outcomes.”

- context can be made up of cultural factors like geographic location and/or particular gender or racial-based interests. In some reviews, context can also include information about the particular setting.

Adopting the PCC mnemonic also enables the reviewers to craft a title that conveys important details to readers, e.g., the focus and scope of the review as well as how the reviews can be applied to their needs. In a nutshell, the PCC concept is necessary to establish concord between the title, review question(s), and inclusion criteria.

Scoping review question(s)

Just like the title, the scoping review question(s), should also reflect the PCC elements. The question guides and directs the reviewers to develop inclusion criteria that are suitable for the scoping review. Moreover, a clearly expressed question helps in constructing the protocol, makes for an optimal literature search, and offers a clarified structure for developing the scoping review. A Scoping review will usually come with only one primary question. For example,

Are there any side effects in the various treatments for depression?

However, sub-questions may be necessary, especially if the primary question neither sufficiently reflects the PCC nor the review’s objective(s). In such a scenario, sub-questions can help shed more light on the specific characteristics of a population, concept, or context. Sub-questions can also help to highlight the most likely way to map evidence with respect to the PCC elements. Using context, for example, the above primary question which deals with just the side effects of depression treatments can be expanded to:

Are there any geographical contexts that depression treatments have been associated with side effects?

Introduction

The introduction should be broad enough to capture all the key elements of the topic being reviewed. It should include the reason for carrying out the scoping review (including the rationale behind each of the elements as well as the information the review intends to disseminate in addition to the objective(s) of the review.

Be sure to explain any definitions that are relevant to the topic under review. You should also ensure that the introductory information must be presented in a way that sufficiently sheds light on the inclusion criteria. For instance, information about the existence or otherwise of scoping reviews, systematic reviews, research syntheses, and/or primary research papers on the topic. This will help reinforce your reason or rationale for undertaking the scoping review.

The concluding phase of the introduction should indicate that the reviewer has already conducted a preparatory search for available scoping reviews (and maybe systematic reviews as well) on the topic. The dates of such searches, the databases, and journals searched and search platforms used must also be included. Some examples in this regard include the JBI Evidence Synthesis, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

If scoping and/or systematic reviews about the topic are available, the reviewers then have to clearly justify how their proposed review will differ from those they have identified. This will enable readers to easily determine any new insight or knowledge which the forthcoming review espouses when compared to existing evidence syntheses.

Finally, the concluding phase of the introduction should explain how the review’s objective(s) align with the main elements of the inclusion criteria, for example, the PCC.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria capture the reviewers’ reasons for selecting which sources that will be part of their scoping review (or otherwise). These reasons should be clearly explained in a way that enables readers to easily comprehend the reviewers’ ideas. As stated earlier, there must be concord or synergy between the title, question(s), and inclusion criteria.

Search strategy

Even with time and resource constraints, the search strategy for a scoping review should try to be as broad-based as possible. This will help the reviewers to fish out both published and unpublished primary sources of evidence and reviews. The reviewers should endeavor to narrate and rationalize any limitations that negatively impacted the scope of their search strategy.

It is recommended that the search strategy follows the three steps enumerated below.

1) Conducting a preliminary search on not less than a couple of web-based databases determined to be relevant to the topic.

2) A second search that includes all identified keywords and index terms to be conducted on all the selected databases.

3) Identified reports and articles should be searched.

The reviewer has to specify both the languages he or she will consider for inclusion and the timeframe. They should also provide clear reasons for such specifications. To ensure an optimal search strategy, several search iterations may be necessary especially if the evidence base becomes clearer to reviewers thus leading to the knowledge of additional keywords, sources, and search terms. Because of this possibility for repetitions, it is very essential to ensure that the whole search strategy is characterized by transparency and audit capacity. To this end, a research librarian or information/data scientist can be a useful partner to help design and refine the search strategy.

The process of conducting a literature search can itself be divided into 5 steps:

- Decide on research question(s) in your specific subject area

- Find relevant databases you will search

- Create a list of relevant keywords and phrases for your literature search

- Begin the literature search while taking notes from each database to keep track of your queries

- Begin the scoping review and compile your results into an article

- If needed, revise your original research question(s)

Source of evidence selection

A scoping review protocol should include a description of all the stages of the source selection process based on title and abstract examination as well as on full-text examination. It should be premised on the inclusion criteria and also explain the mechanisms for resolving disagreements among reviewers. The source selection (both the title and abstract examination and the full-text screening) should be conducted by a couple of reviewers or more. Disagreements arising between the reviewers can be resolved either by consensus or by a third reviewer.

The process should be explained through a narrative description which has to include a flowchart of the review process (from the PRISMA-ScR statement). The chart shows the flow from the search through source selection, duplicates, full-text retrieval, and all inclusions from the third search, data extraction, and presentation of the evidence.

Information on the retrieved full-text articles should be provided. Separate appendices providing information on included sources should also be provided. The appendices should briefly disclose all excluded sources as well as the reasons for their exclusion.

The reviewers should mention the software used to manage the results of the search. Examples include Covidence, JBI SUMARI, etc. Before venturing into source selection across a team, it may be necessary to pilot test the source selectors to enable the team to refine their source selection tool (assuming they are using such a tool).

Data extraction

The data extraction process is often referred to as “data charting” in scoping reviews. Data charting is a logical and descriptive summary of the results which are in alignment with the objective(s) and question(s) of the scoping review. It is necessary to construct and pilot a data charting table or form during the protocol stage. This will help the reviewers to record important details about the source such as those below.

- Author(s)

- Publication year

- Origin/country of origin (where the source was published or conducted)

- Aims or purposes

- Population and sample size within the source of evidence (if applicable)

- Methodology / methods

- Intervention type, comparator, and information on these (e.g. duration of the intervention) (if applicable). Duration of the intervention (if applicable)

- Outcomes and information on these (e.g. how it was measured, if applicable)

- Important findings relating to the scoping review question(s)

These details can be refined in the review stage albeit this will necessitate an updating of the charting table. Careful record-keeping is necessary on the part of the reviewers since it will ensure ease of reference and tracking as well as help them to identify and chart every source as well as any other additional unanticipated data. This implies that charting the results can be a repetitive process of continuous updating of data.

In summary, it is very important that the reviewers exhibit transparency and clarity in their data extraction methods. Like in source of evidence selection, pilot testing is also necessary.

Analysis of the evidence

Many scoping reviews are usually analyzed through simple counting of concepts, populations, characteristics and so forth. However, other reviews may need a more complex analyses, e.g., descriptive qualitative content analysis which includes basic coding of data.

For quantitative data, more sophisticated techniques can be utilized instead of simple frequency counts to determine the occurrence of concepts, characteristics, populations, etc. However, such in-depth analyses are not common in scoping reviews. Areas like meta-analysis and interpretive qualitative analysis have very small probabilities of being used in scoping reviews.

The nature of data analysis in scoping reviews is largely determined by the purpose of the review and the reviewers’ evaluations. The most vital concern is the level of transparency of the analytical method used and the ability of the reviewers to rationalize their approach in addition to a priori planning of the review.

Presentation of the results

It is important provide a plan for the presentation of results (one that includes the type of charts, tables and/or figures that will be used) during protocol development. The essence of early planning is to have some knowledge of the kinds of data that might emerge and the best way to present such data with respect to both the objective(s) and research question(s) of the scoping review. This knowledge can be modified during the review process when the reviewers must have become more aware of all data from the included sources.

It is possible to present the results of a scoping review in a descriptive format and/or as a map of the data from the included sources, e.g., tables and other diagrams. The PCC concept can be an essential guide on how to map data efficiently.

More info

For more information regarding scoping reviews, please refer to Arksey, H. and O’Malley paper [1] or JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [2], this article is based primarily on the latter source.

✅ Also check out

This post was produced as part of a research guide series by Avidnote which is a free web-based app that helps you to write and organize your academic writing online. Click here to find out more.

References

Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2008;6(1):1.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Arksey, H. and O’Malley paper (2015). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology, 8(1), pp.19-32.

Colquhoun, H.L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K.K., Straus, S., Tricco, A.C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M. and Moher, D., 2014. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 67(12), pp.1291-1294.

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Source: https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/11.2.6+Source+of+evidence+selection

Munn, Z., Peters, M.D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A. and Aromataris, E., 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology, 18(1), pp.1-7.

Osman, M.A., Schick-Makaroff, K., Thompson, S., Featherstone, R., Bialy, L., Kurzawa, J., Okpechi, I.G., Habib, S., Shojai, S., Jindal, K. and Klarenbach, S., 2018. Barriers and facilitators for implementation of electronic consultations (eConsult) to enhance specialist access to care: a scoping review protocol. BMJ open, 8(9), p.e022733.